Off to a wānanga

Granted a science journalism award for an iwi-based bioheritage story, I head to a wānanga at Te Hapua marae in the Far North

Wednesday November 21, 2018

11:00am, Wellington Airport

The wind’s changed to a gentle southerly. It’s spring in the capital and a brisk 16 degrees outside. Inside the airport, suits clutching briefcases, parents driving pushchairs and teams of kids with heads in devices heat up the sprawling space.

A giant eagle looks like it’s about to swoop down from the roof and skewer me with its talons. But the enormous hanging sculpture is just a reminder we’re in Middle-earth. Out the window I see a brushstroke of watery sun blend into the clouds. I’ve packed my thermals even though I’m off to a wānanga in the winterless north.

4:00pm, Kerikeri

Finally, after delays in Auckland, I’m in my tiny rental car whizzing further up country. From Kerikeri along State Highway 10 to Awanui then on to State Highway 1 (after a wrong turn to Kaitaia) and I’m getting closer. It’s 183 kilometres and should take me two hours 38 minutes. But it takes me longer.

From Awanui, I’m in the rohe of Ngāti Kurī, one of New Zealand’s northern-most iwi. I’ve been invited to a wānanga at Te Hiku o te Ika Marae in Te Hapua, a coastal hamlet on the shores of Pārengarenga Harbour. “Just get yourself here,” says Ngāti Kurī trustee and wānanga organiser Sheridan Waitai down the phone, “we’ll look after you after that.”

Over three days, I’ll learn about the iwi’s growing relationship with New Zealand’s science community and more about its plan to completely transform the region into an ecosanctuary with a $1.2 million predator-proof fence.

I’ll listen to pepeha and stories of the country’s largest Treaty claim called the WAI 262. I’ll dry dishes, scramble eggs and sleep on a mattress next to snoring aunties and a sleeptalking teen.

One morning, I’ll rise early to watch a blazing pink sunrise over the harbour. I’ll sing waiata, talk science and hear stories of Te Hapua’s wild horses. “They’re like part of the whānau,” I’m told over a cup of tea as a surly miniature pony walks past. “As a kid, you’d go up to one, grab its forelock and jump on until you got to where you needed to go or it’d had enough of you, whichever came first. Us kids and those horses had a special thing going on.”

Te Hapua sunrise over Pārengarenga Harbour (image by Jacqui Gibson).

Te Hapua pony (image by Jacqui Gibson).

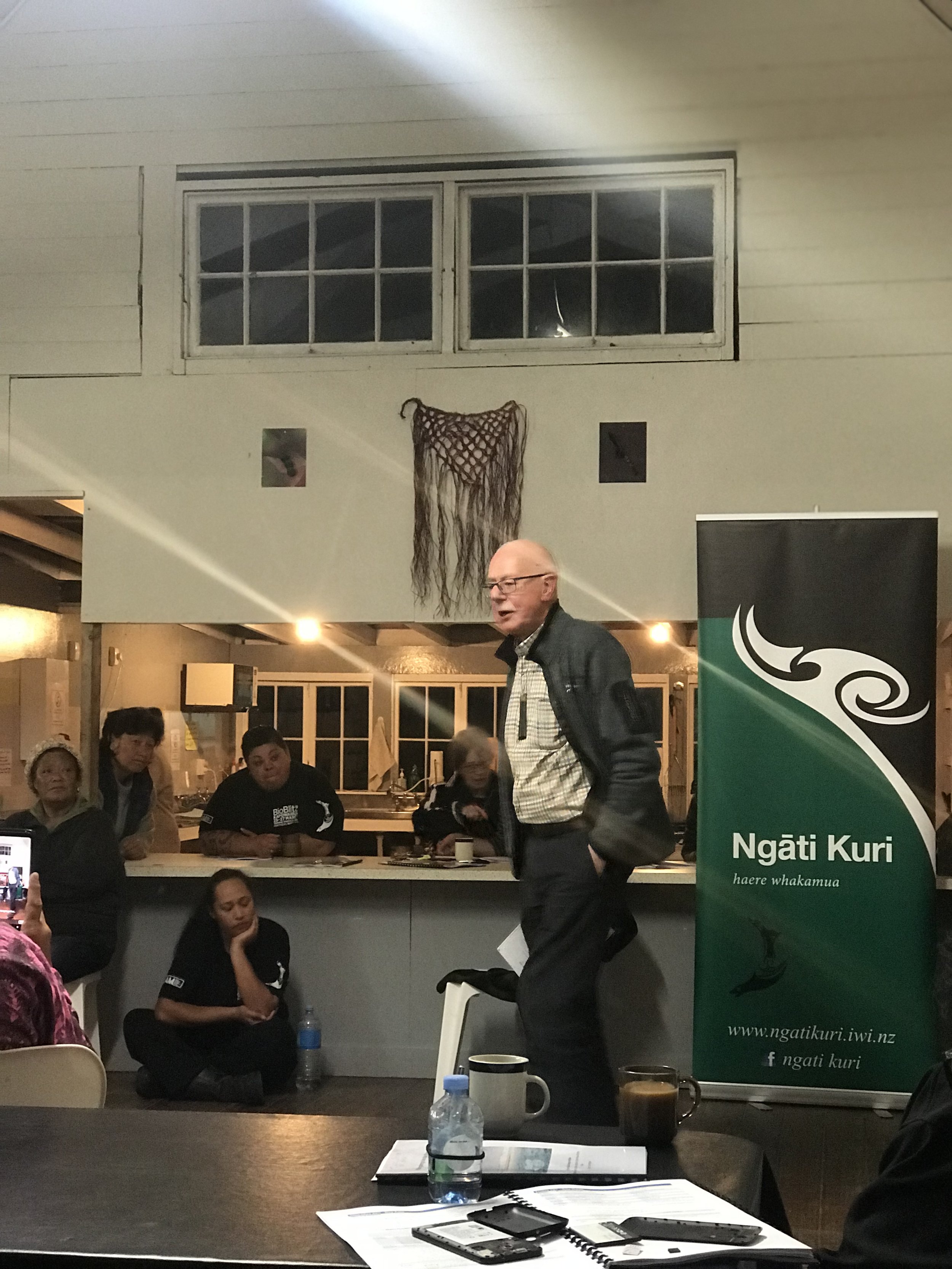

8:00pm, Oliver Sutherland takes the floor

Tonight, there’s nearly a hundred people packed into the dining room. We are iwi members, researchers, writers and scientists from organisations like the Auckland War Memorial Museum, the Department of Conservation and the regional council.

Oliver, a former DSIR scientist from Nelson, and his wife Ulla Skold have come to Te Hapua to speak publicly about Oliver’s 40-year relationship with Ngāti Kurī.

It was Oliver and the late Ngāti Kurī kuia Saana Waitai-Murray who, together, challenged the monocultural approach of New Zealand’s science institutions and started using both Western science and mātauranga Māori to promote the cultural and economic interests of the iwi.

Former DSIR scientist and long-time supporter of Ngāti Kurī, Oliver Sutherland (image by Jacqui Gibson).

Oliver tells us he and Saana successfully set up a weaving co-op in Te Hapua, which sold Northland kete to stores like Modern Bags in Auckland and later Trade Aid and eventually raised money to build Te Hapua’s arts and craft centre.

The pair led a series of horticultural land trials of crops like pineapples, tamarillo and peanuts and helped launch Ngāti Kurī’s now-thriving mānuka honey industry. For decades, they hosted visits to Te Rerenga Wairua (Cape Reinga) by DSIR entomologists keen to collect rare and unusual insect species for the New Zealand Arthropod Collection.

In 2010, a new genus and species of stick insect was discovered, with naming rights assigned to Saana – a year later Tepakiphasma ngātikurī was written into the science books.

Te Hapua kete display (image by Jacqui Gibson).

Oliver and Saana each played a role in setting up DSIR’s first-ever meeting with Māori leaders at Auckland’s Owairaka Research Centre in 1985. And they were behind New Zealand’s inaugural ethnobotany workshop held at Rehua Marae, which brought together more than 200 people representing Western science and traditional Māori and Pacific knowledge.

As part of a bigger, collective effort led by lawyer Moana Jackson, they joined forces to put a stop to plans to commercialise native plants such as mānuka and helped draft a Treaty claim known as the WAI 262.

The claim, lodged by Saana and five others in October 1991, explains Oliver, was audacious and far reaching in scope, and essentially sought Māori control over things Māori. (Things like kūmara, pōhutukawa, koromiko and puawānanga and animals like pūpū harakeke, tuatara and kererū).

It took the Crown more than 20 years to respond to the claim, which remains unresolved for the most part, Oliver tells us. But, thanks to Ngāti Kurī’s new plan to transform the region into an ecosanctuary and because of the people here tonight, its legacy lives on.

Before we break for a cup of tea and bed, Oliver wraps up by saying the relationship between some of New Zealand’s leading scientists and Ngāti Kurī has endured because of the respect and trust of the people involved.

“That’s the lesson here. Looking back, you can see those kaumātua trusted us, as scientists, to cherish and value their taonga species and the knowledge – both traditional and scientific – of those species.

“It’s my sincere wish that the trust of those kaumātua, none of whom are with us now, will continue to be honoured by New Zealand’s science community in the years ahead.”

10.00pm, Te Hapua

As I slip into my sleeping bag, I think about this relationship and wonder if it’s the way ahead for science in New Zealand? A prototype for partnership?

Thursday

9:00am, Pārengarenga Harbour field trip

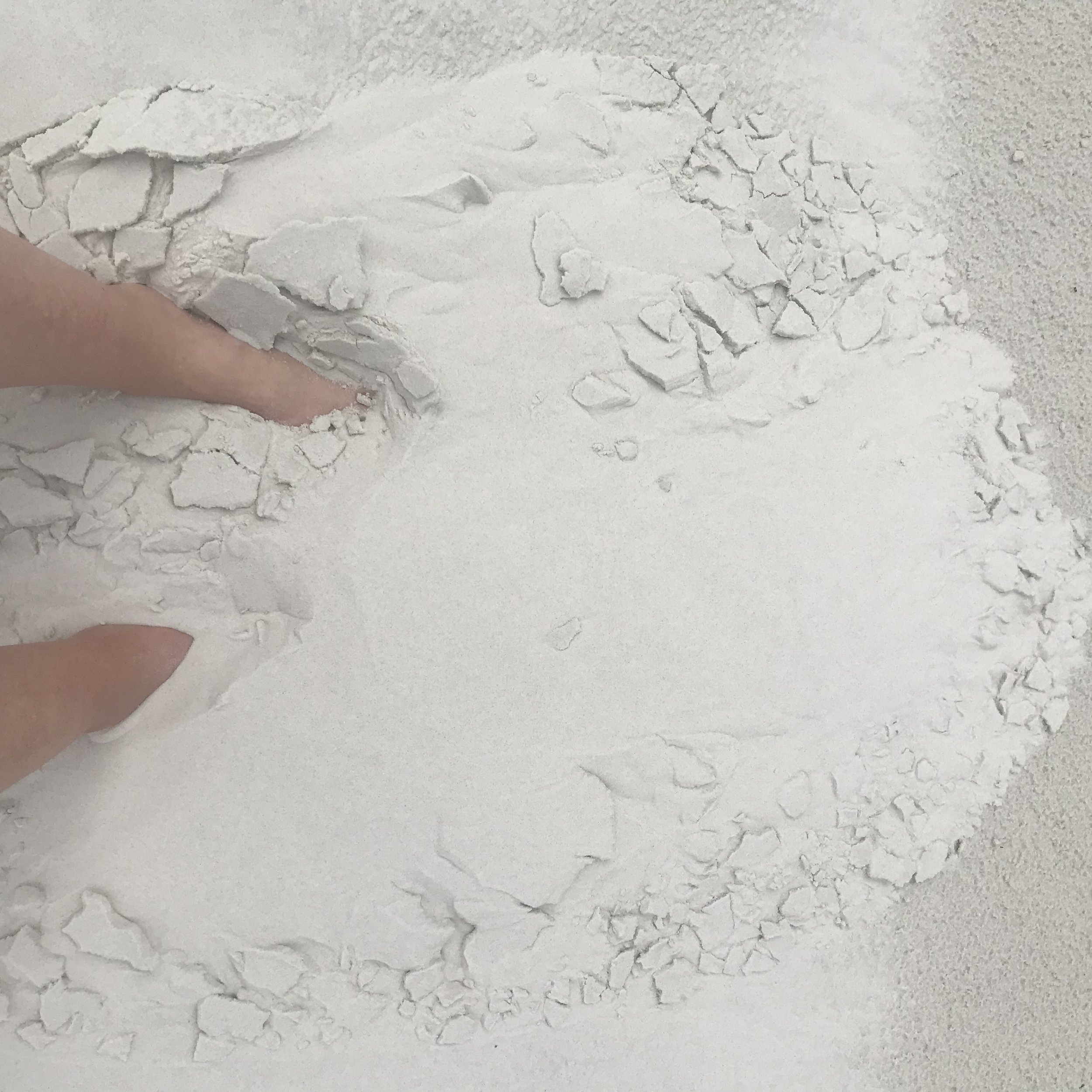

Mōrena. A soft rain is falling this morning, yet the water is still an impossible turquoise green and the sand dunes seem to glow like a night light in the distance.

After breakfast we jump on oyster barges and head out across the harbour to Te Kokota spit. The scientists are fizzing. Kids are wide-eyed. I roll up my trousers, tug my lifejacket into place and wade into the harbour to join my fellow travellers on a metal waka.

Today’s field trip is bi-cultural science in action.

On the water, Aunty Rose recounts a century of mining the pristine silica dunes by private companies like Auckland’s ACI for glass operations in Penrose. Ngāti Kurī never received a cent in royalties and finally put a stop to dredging in 1997.

“It was devastating for our tribe. These waters are the habitat of green sea turtles, dolphins, orca and other whales. The suction method ruined our pīngao. The slush buried our pipi and huawai beds and the mullet weeds that were the spawning grounds of our fish. Our old people used to talk about a time when the dunes were like mountains.”

Heading to the white sands of Te Kokota (image by Jacqui Gibson).

Silky silica sands of Te Kokota, Far North (image by Jacqui Gibson).

An afternoon in the sand dunes

On land, we encircle Ngāti Kurī weaver whaea Betsy Young as she explains how to harvest and weave the burnished gold pīngao growing vigorously among the silky sand under foot.

I duck off to follow Auckland Museum botany curator Ewen Cameron. He’s collecting specimens for the museum’s herbarium. In previous visits to the Far North he’s found native plants like tanekaha and a special kind of koromiko.

Other scientists, like Otago University zoologist Nic Rawlence, have found ancient fossils on Ngāti Kurī land. Eric Edwards, a Department of Conservation entomologist, carried out a stocktake of the insect species of the region as part of a plant and animal audit earlier this year (I see some of Eric’s impressive collection on display in the dining hall later that night).

These scientists are just a handful of people working with Ngāti Kurī to understand and document the environmental character and bioheritage of their land, as well as plan for its regeneration.

Te Hapua pīngao (image by Jacqui Gibson).

Auckland Museum botany curator Ewen Cameron’s samples from Kokota spit (image by Jacqui Gibson).

8:30pm, back at Te Hapua

After dinner I meet Les Feasey, from Birds New Zealand. He’s another scientist chipping in data to the iwi’s knowledge base.

In Pārengarenga, he explains, there’s been a dramatic decline in a Ngāti Kurī-prized bird species, the kuaka (or bar tailed godwit), from 4,500 birds five years ago to about 700 birds last summer.

Extraordinarily, this taonga species with its long tapering and slightly upturned pink and black bill, breeds in Alaska and migrates to New Zealand and eastern Australia. It’s sadly in decline throughout New Zealand – and nowhere more so than here.

Friday farewell

Grouped under an outdoor tarpaulin, we sip tea as rain continues to fall. This morning, we watch presentations from Ngāti Kurī’s scientific partners.

The story of the iwi’s declining bioheritage is stark. While some taonga species like Pūteretere, Tecomanthe speciose, are doing well, others need immediate care. Overall, pīngao is not in a good way. Ngāti Kurī’s much-treasured Rātā moehau, Metrosideros bartlettii, despite a tentative foothold in nearby Te Paki and Spirits Bay, has been deemed the most threatened tree species in the country.

That’s why Ngāti Kurī’s relationship with the science community is so important, says kaumatua Wayne Petera. “As we build relationships with the Auckland War Memorial Museum and the science community we create pathways to mana motuhake and tino rangatiratanga. Our autonomy and self-determination to claim and engage with our taonga species, mātauranga and whakapapa is strengthened. My challenge to our science community remains: How will each of you, as organisations, and as individuals, continue to contribute to our vision?”

Eric Edwards’ ecology display, Te Hapua marae (image by Jacqui Gibson).

Te Hiku o te Ika Marae, Te Hapua (image by Jacqui Gibson).