Women, take the matter up

New Zealand women were granted the right to vote 125 years ago thanks to suffragists like Kate Sheppard and Meri Te Tai Mangakāhia. So how have women in the public service fared since 1893? Jacqui Gibson catches up with some women of the public service to find out

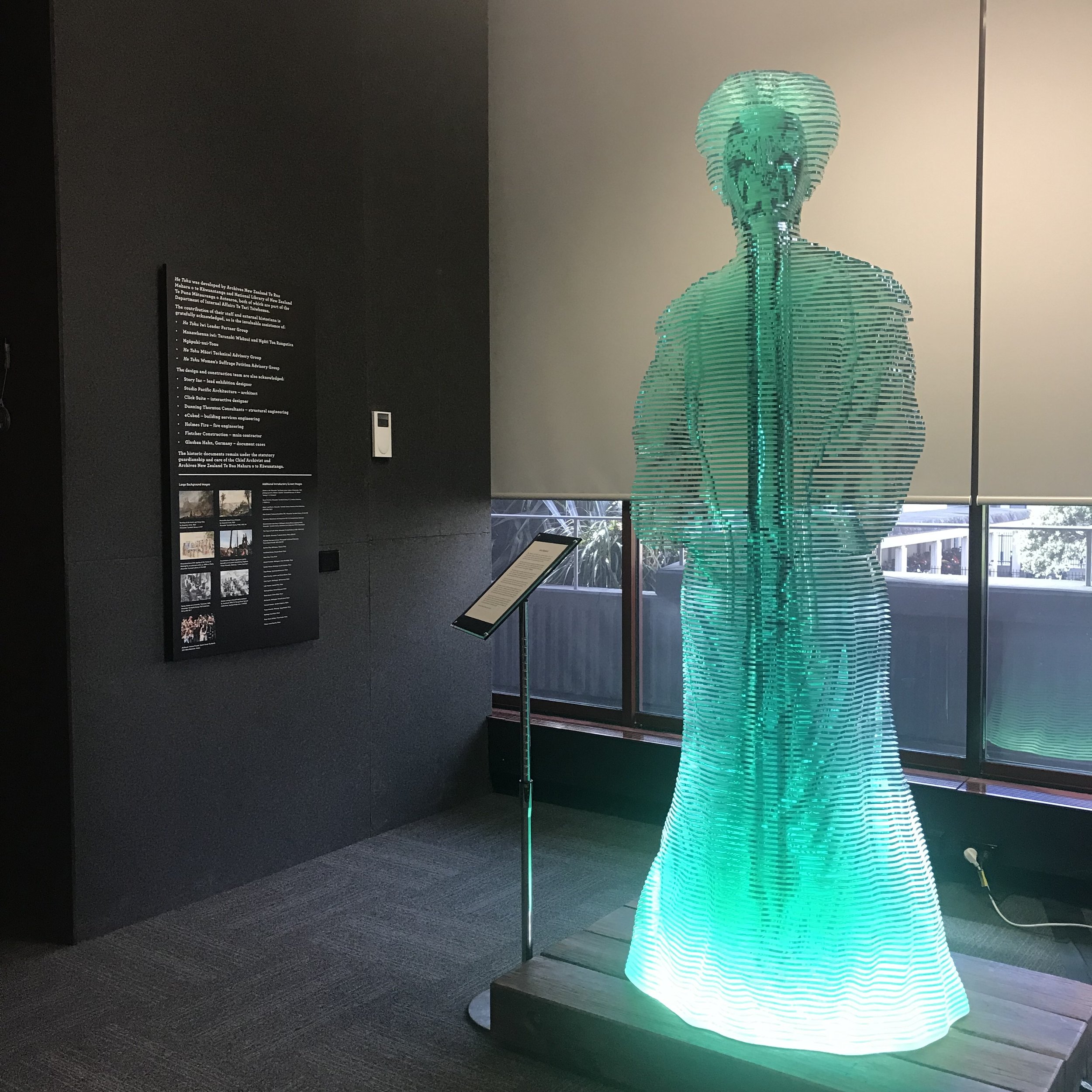

New Zealand Parliament buildings, Wellington (image by Jacqui Gibson).

Acting chief executive of Ministry for Women, Helen Pōtiki, and I are seated at a small round table in a glass-walled office on The Terrace, Wellington.

I’m embarrassed. We’re not long into our interview, and my pen has run out. Damn it. Not a good look.

Before I know it, Helen is out the door and back again with a fist full of pens, each one loaded with ink and ready to go.

She’s like that – a senior public servant who believes in manaatikanga and empowering others through actions big and small. On the one hand, she’s clocked up more than 15 years advising the powers-that-be on issues such as gender equality and flexible work, frequently representing New Zealand on the world stage.

On the other hand, she’s a career coach, mentor, and sponsor to a handful of women at different levels of central government and the non-government sector.

“I see it as my professional responsibility to elevate other women,” explains Helen, of Ngāti Porou, Tapuika, and Ngāi Tahu descent. “Yes, it’s wonderful to rise to a chief executive position. Women are not short on talent, ability, or ambition, but a woman’s path to a chief executive role is quite different from that of a man’s.”

Women in the public sector

Data shows that while women make up the majority (61 percent) of the country’s 350,000 public sector workers, they represent 45 percent of senior management and 12 out of 29 chief executives.

Women are over-represented in government administration and clerical roles (at 82 percent), while making up just 33 percent of the IT labour force.

And women, overall, within the public service earn 12.5 percent less than men, with the gender pay gap as high as 39 percent in some agencies.

Women, overall, within the public service earn 12.5 percent less than men, with the gender pay gap as high as 39 percent in some agencies …

“I’d say most women today become leaders through hard work, grit, and by having someone in their corner who believes in them, helps them, and has their back,” says Helen. “It’s much less because of the systems or institutions in place.”

That’s why 125 years of women’s suffrage still matters.

Across the road, Penny Nelson, deputy director general for Policy and Trade at the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI), agrees.

“We are seeing some success in government. We do have women chief executives. We have a woman prime minister. The main challenge is that this is not the norm. We’re still talking about women in leadership as if it was unusual or newsworthy.”

Penny Nelson, deputy director general for Policy and Trade at the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI). (Photo supplied).

Penny, while new to her MPI job, has more than 20 years’ experience in the public and private sectors.

She’s worked for DairyNZ, the Sustainable Business Council, and Landcare Research. Her last role was deputy secretary at the Ministry for the Environment.

“Throughout my career, I’ve always had women leaders who developed and mentored me. I had a couple of years out of the workforce after my partner and I had our first child. When I came back to work, my manager backed and challenged me. That made a huge difference. She’s been a great influence – and I aim to pay it forward in the same way.”

Historic gains for women

From the Public Service Association (PSA) office in Wellington’s CBD, national secretary Erin Polaczuk says her organisation has a proud history of making gains for women in the public sector.

Founded in 1913 – a year after the public service formed – the PSA dates back to when women could only take up shorthand and typing jobs. Once married, they were expected to resign.

Thankfully those days have long since gone. But it’s been a battle, says Erin.

“We’ve fought against the long-standing belief a woman’s income was only ever supplementary to her husband’s. For years, the prevailing thinking among public sector leadership was if you can buy a woman’s labour for less, you should.”

Public Service Association (PSA) national secretary Erin Polaczuk. (Photo supplied).

Equal pay

Erin says equal pay became a full-scale campaign for the PSA in the 1950s. But it took another decade before parliament passed the Government Services Equal Pay Bill to introduce equal pay to the public service. The private sector finally followed suit in 1972 with the Equal Pay Act.

“Despite all this, we’re still not there. Yes, it’s disappointing. Pay equity was a right the suffragists pushed for back in the 1890s. But I think we’re starting to see momentum build again.”

A good example is the Equal Pay Amendment Bill, announced on 19 September to mark the 125th anniversary of women’s suffrage. The law essentially makes it easier for women to make claims for fair and equal pay.

In July, the Minister of State Services and the Minister for Women, together with the PSA, announced a joint action plan to eliminate the public service pay gap by 2020.

Agencies are now required to report on the gender pay gap within their organisations and say what they are doing to address it.

The State Services Commission has a new working group tasked with increasing flexible work conditions and leadership diversity.

Training is being rolled out across the public service, recognising “unconscious bias” as one of the main barriers to closing the gender gap.

Agencies are exploring the transparency and accessibility of information about pay. Remedying the negative impact of leave and caring duties on female employees is another priority.

Meanwhile, the PSA continues to pressure agencies to improve the lot of women employed at the lower grade jobs of the public sector.

Negotiating for more favourable collective agreements, parental leave conditions, and leave related to tangihanga and domestic violence are just some of the PSA’s more recent wins.

Workplace culture

Halley Wiseman is a resource consents manager who joined Wellington City Council 17 years ago.

Today she manages a team of 20 city planners in a role she loves because “no day is the same” and because it gives her an opportunity to shape the city.

Halley believes the culture of the council is changing for the better.

“In the past few years, there has been a real drive from the executive leadership team to create a more inclusive and positive culture among employees, no matter who you are.

“We’ve refreshed our vision, values, and behaviours and set up a cross-council equality, diversity, and inclusion policy working party.”

In time, she’d like to think the working party will help bring about a more ethnically and gender diverse workforce.

“I’ve sat in many meetings over the years where I’ve been the only female. I learned very quickly to hold my own. That’s my advice to women in local government. Hold your own – you have a voice and a view that counts.”

Government Women’s Network

Liz Chin, from the Department of Internal Affairs, is keen to see advice like Halley’s shared and practised by all women in the public sector.

So in August last year, she took up a secondment as programme director for the Government Women’s Network (GWN) – an all-of-government group based at the Ministry of Justice.

The goal of GWN is to support women and help government agencies become better employers and improve the services they offer by allowing for greater gender diversity.

As programme director, Liz acts as the link between agency networks and GWN’s broader team – a nine-person governance group that includes GWN’s Auckland and Southern chairs.

“I’m there for initial support and advice when networks are getting started. But it’s up to each network to figure out the issues they want to tackle, how to operate, and what funding may be available.”

The common goal of every network is to promote the interests of women in the workplace and help members achieve their goals. So far, more than 45 networks have set up around the country, says Liz.

A recent example is the Southern Government Women’s Network based in Christchurch, which started in May. In June, one of the more well-established networks took out the Empowerment Award at the annual Diversity Works New Zealand Awards.

Based at the Ministry of Justice, the network has 730 members from Kaikohe to Invercargill, as well as a team of 25 volunteers who run monthly events and arrange development opportunities. It operates during work time and is strongly supported by senior management.

This year, it features a Men as Allies campaign, which aims to help men better understand the barriers women face and how to address them.

On Suffrage Day this year, MPI and ACC launched women’s networks of their own.

MPI newcomer Penny Nelson opened a panel discussion to mark the launch of Ngā Wāhine Toa, MPI’s women’s network. The launch was attended by more than 200 staff.

“It was a privilege. I’m still very new here, but from my recent experience, I couldn’t have been better supported as I’ve come in. It’s been great hearing senior leaders discuss the steps we’re taking to become a more diverse and inclusive workplace.

“I think agency leaders understand that being more representative will help us get the most from our people, as well as grow and deliver for New Zealand communities.

“At the network launch, I loved seeing up-and-coming young women leaders take the Suffrage Day legacy forward. Naturally, we have further to go, but it’s exciting to think of a more diverse public sector. And I hope we achieve that well within the next 100 years.”

This story was first published in the Public Sector Journal.

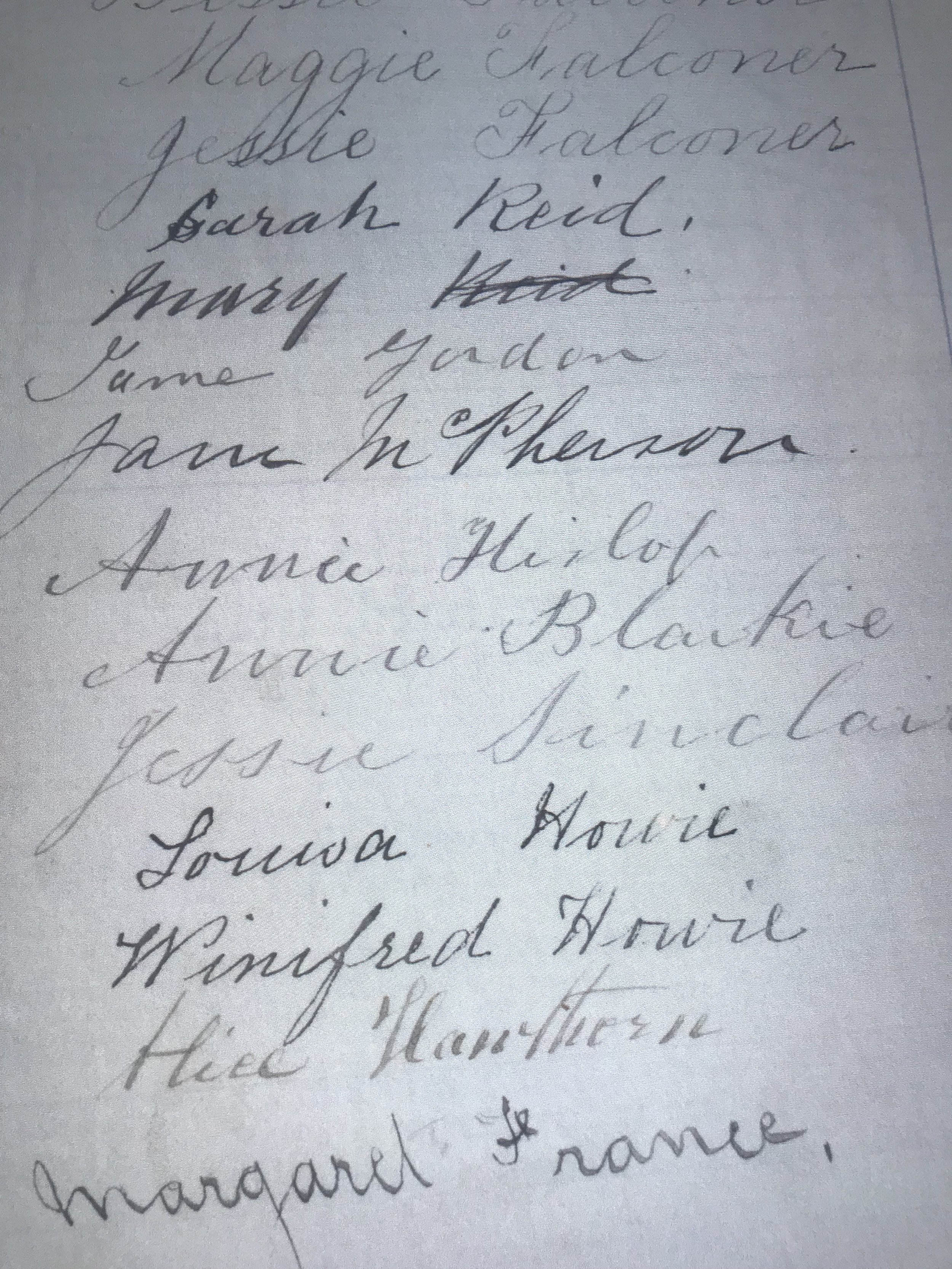

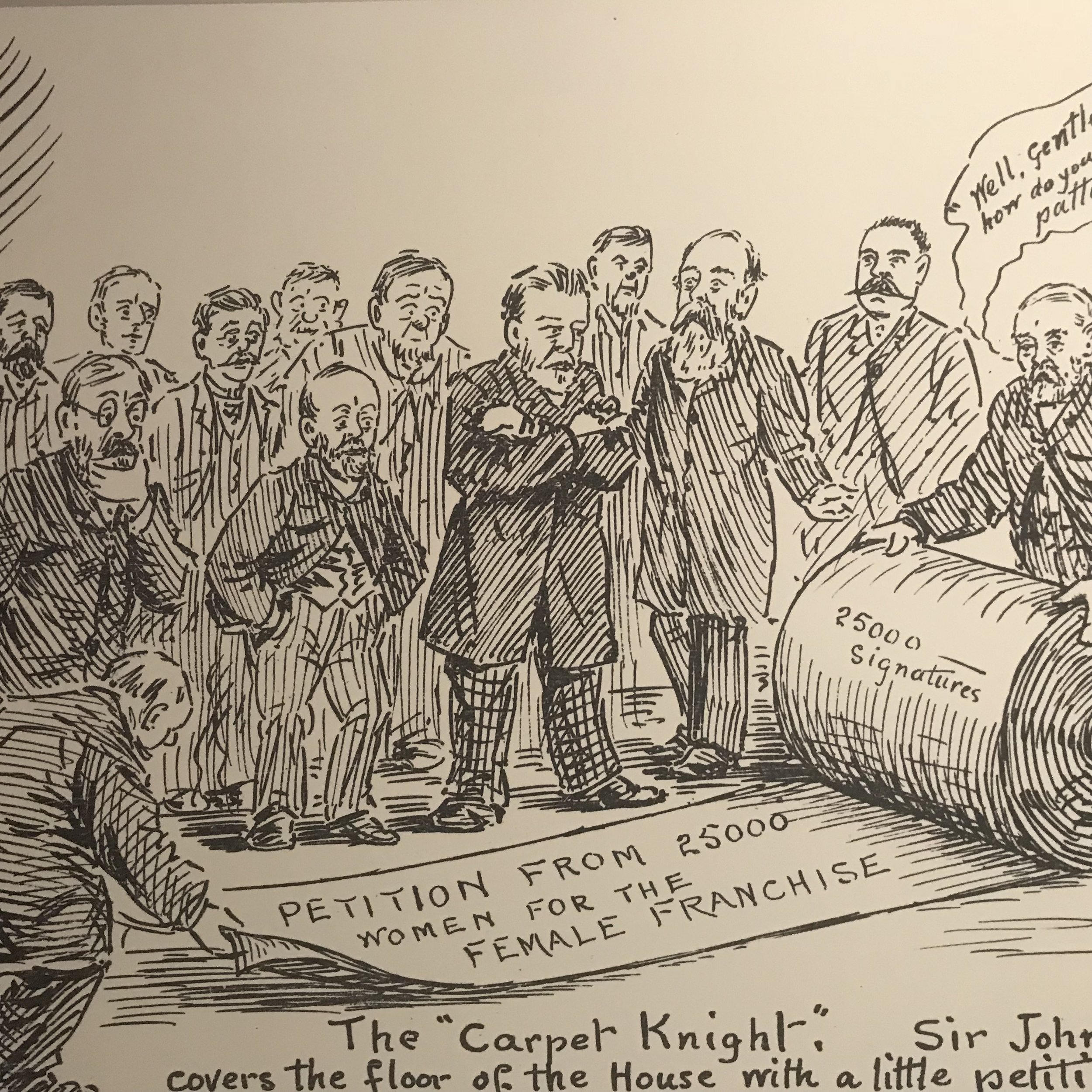

Flashback to 1893

Women vote for the first time on 28 November 1893.

On polling day, 90,000 women voted (an 82 percent turnout, far higher than the registered male voter turnout).

There were no female candidates to vote for (women would wait another 26 years before they could stand for election).

New Zealand’s first female MP, Elizabeth McCoombs, was elected 40 years later.

Today, New Zealand sits at 19th in the world for the number of women MPs in parliament.