A walking tour of Wellington’s Modernist icons during Wellington Heritage Week

What parts of a city would you forgo in the name of progress and what parts would you hang on to? Jacqui Gibson takes walking tour of Wellington’s Modernist icons

Lambton Quay, Wellington. (Image by Nicola Edmonds courtesy of wellingtonnz.com)

It's a sunny Sunday afternoon in Wellington's CBD.

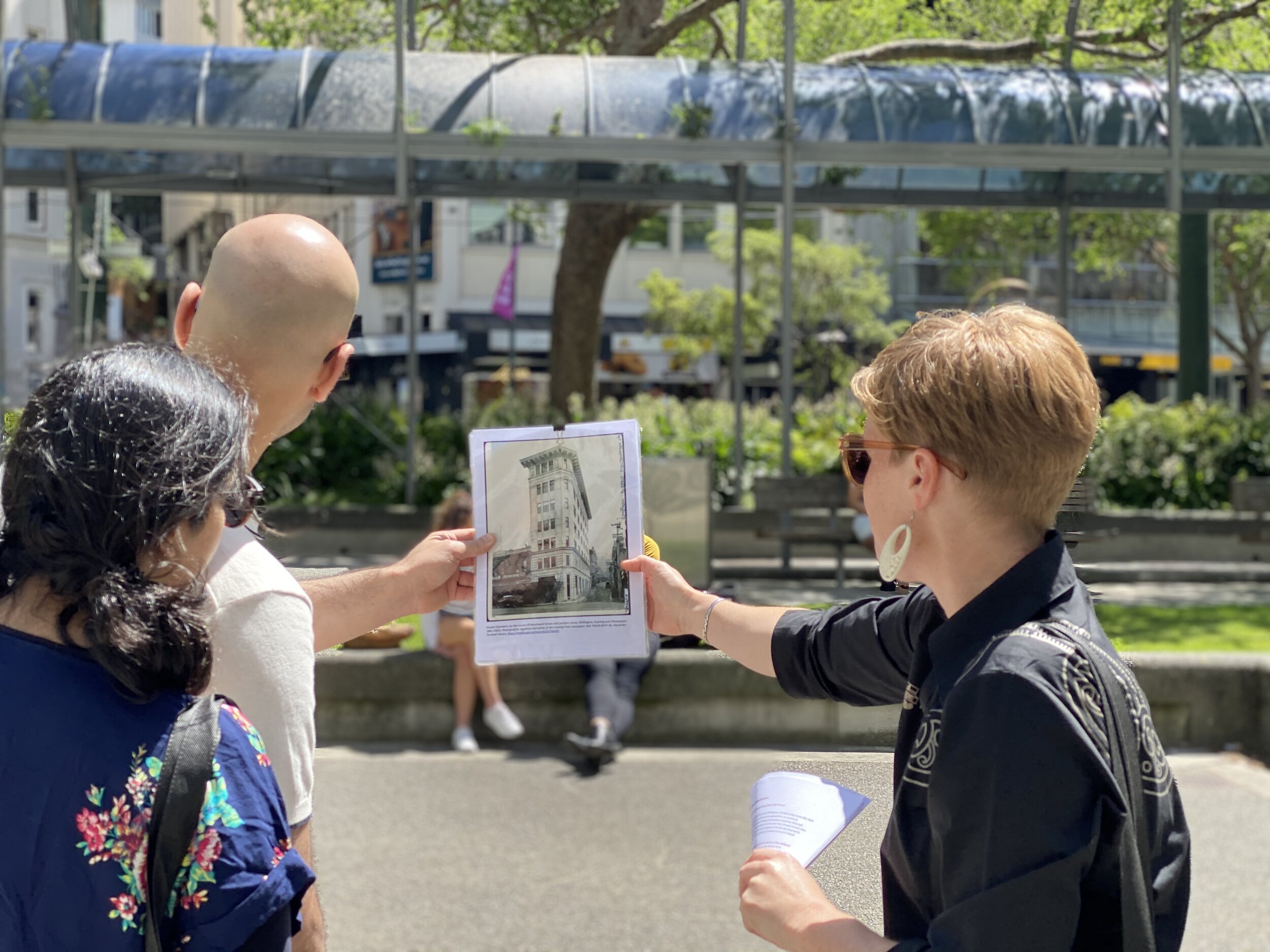

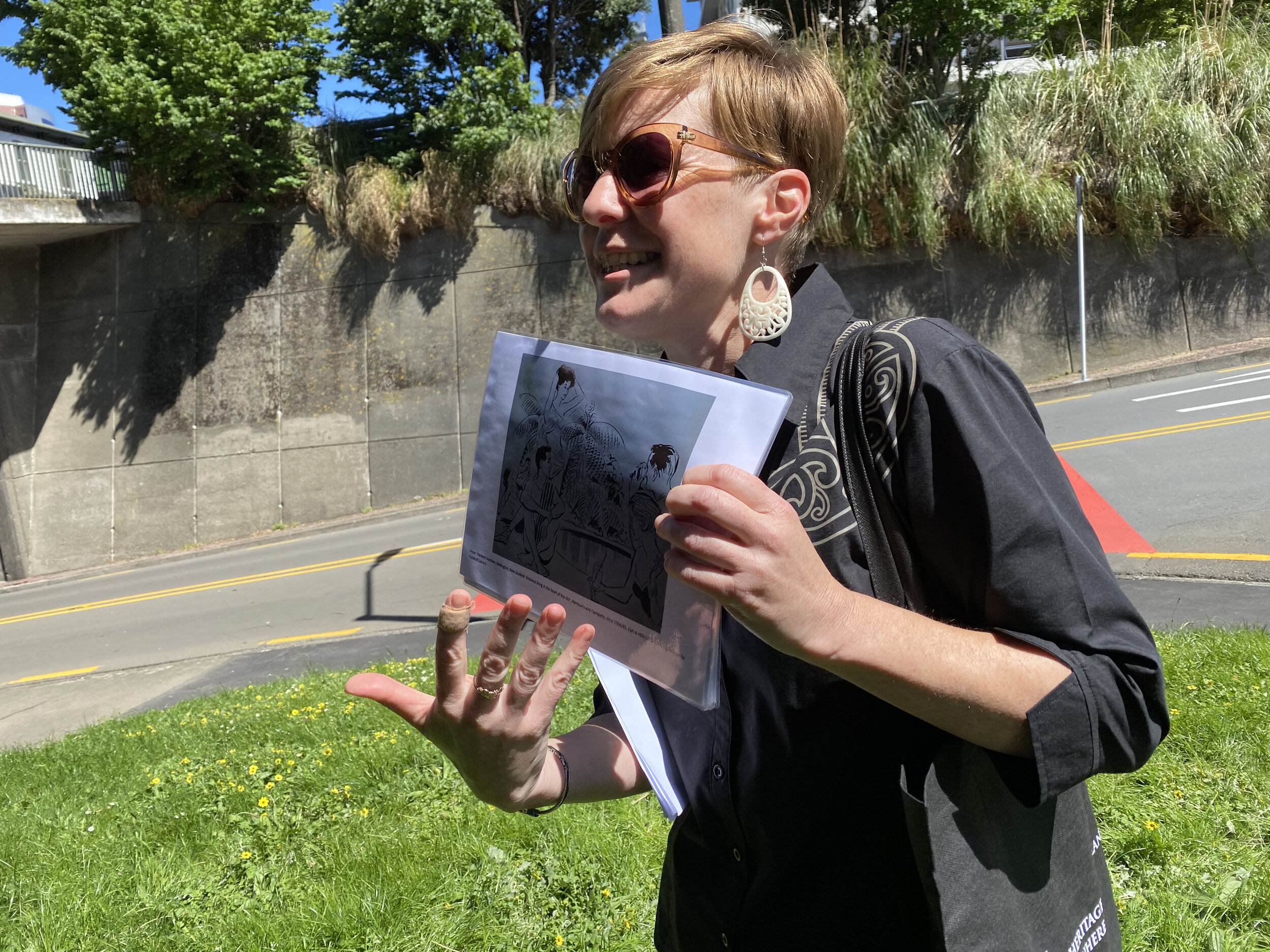

Six of us are crowding around Karen Astwood, Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga tour guide, leaning in to hear her speak over the commotion of wind and traffic.

We’re the final stragglers in a group of more than 30 people who’ve turned out for today’s Modern Wellington Tour on the final day of Wellington Heritage Week, an annual festival in its fourth year.

This year, Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga is a major sponsor of Wellington Heritage Week and has six events in the festival line-up.

When I catch up with festival director and founder David Batchelor a week before the tour, he tells me Modernism is hot right now.

“The question is: do we save Wellington’s Modern heritage or get rid of it to make way for development? Do buildings less than a century old qualify as heritage? Do we even like the look of these often pared back buildings?

“These are the sorts of things people are talking about it. I don’t have the answers. But it’s wonderful to have agencies like Heritage New Zealand and speakers like Auckland University’s associate professor Julia Gatley and senior lecturer Bill McKay championing the topic at Wellington Heritage Week.”

Karen tells us it’s the second year she’s hosted the tour. Both years the tours have sold out.

“People are clearly interested in the topic. And it’s great you’re here.”

The goal of today’s 90-minute tour, she explains, is to showcase Wellington’s Modern heritage and to help people better understand where it came from.

“This tour is really a story about the huge social and cultural change that swept through Wellington in the mid-to-late twentieth century. The buildings we see along the way tell that story.

“Up until the 1940s, Lambton Quay had a small town, Edwardian feel, characterised by low rise buildings with classical facades. By the end of the 1980s, it would’ve been hard to recognise the city. Most buildings were brand new.”

After checking we’re all wearing good walking shoes and have plenty of sunblock, Karen outlines the route.

We’ll start at artist Phil Price’s Protoplasm sculpture, continuing down Lambton Quay to Midland Park. From the park, we’ll head up Woodward Street through the Kumutoto Stream tunnel to a subterranean carpark under the motorway. Next, we’ll walk up to the Terrace, where we’ll cross the motorway, before finishing the tour on the grassy intersection between The Terrace and Everton Terrace.

The first landmark on the trail is the wedged-shaped MLC building, built in 1940 to an Art Deco/Moderne design, on the corner of Lambton Quay and Hunter Street.

From Julia Gatley’s presentation on New Zealand’s Modern Heritage the day before, I learned the 1940s was the decade Modernism took hold in New Zealand.

Pointing skyward to the clock face of the Category 1-listed building, Karen explains the MLC building is both an early example of the city’s Modern heritage, as well as a symbol of a building boom that stretched on until the late 1980s.

“People wanted to move on from the Second World War. They wanted access to new materials and new ways of thinking. They wanted a break from tradition,” Karen tells us, her clipboard papers flapping in the breeze.

The architectural style known as International Modernism reflected this mood exactly, she says, and eventually led to a new-look city.

We learn Modernist architects employed new materials such as glass curtain walling and reinforced concrete. They built everything from glass-clad office buildings to slab apartment blocks to Brutalist hotels.

Wellington’s Dixon Street Flats, completed in 1944 as part of the first Labour Government’s state housing programme (and now a Category 1-listed building) is one of the city’s best examples of Modern heritage.

Lambton’s Quay’s Massey House, the first partially curtain-walled, Modernist building in New Zealand, designed by Plischke & Firth in 1957 and also heritage-listed, is another.

But the new wave of urban development had its downside too, Karen explains as we pause outside Anton Parson’s stainless steel sculpture, Invisible City.

“By the 1980s, it was basically a construction free-for-all. Faced with having to earthquake strengthen Wellington’s older stock of Victorian buildings or upgrade them, private developers tended to tear buildings down.

“The preference was to build high-rise offices and apartments offering better returns. This was so much the trend in the 1980s that at least one major new building was approved by Council every month.”

Walking towards Midland Park, we learn the stunning Spanish mission-style Midland Hotel that occupied the site for more than 60 years was demolished in the 1980s to make room for a new, green space for Wellington’s office workers to enjoy.

At the time, says Karen, city planners, led by pro-development mayor Michael Fowler, wanted to create a more European city with apartment living, cafe culture and public art. They wanted more places to shop and eat. They wanted a more walkable city with better pedestrian access between office life on Lambton Quay and apartment living on The Terrace.

The question is, says Karen, if you were a city planner or mayor: what parts of the city would you forgo in the name of progress and what parts would you hang on to?

The question is, says Karen, if you were a city planner or mayor: what parts of the city would you forgo in the name of progress and what parts would you hang on to?

We ponder this as we trail behind one another up Woodward Street through the Kumutoto Stream tunnel.

After a brief stop to listen to the tunnel’s sound installation by artist Kedron Parker, we gather under Wellington’s urban motorway to discuss the 10-year construction project that displaced thousands of working class residents and exhumed thousands of people buried in the Bolton Street Cemetery.

Later, standing opposite Shell House on The Terrace, we learn the gleaming glass tower completed in 1961, is another prized example of Wellington’s Modern heritage and wonder which ornate Victorian villa it might have supplanted?

According to Julia Gatley, editor of Long Live The Modern, New Zealand’s New Architecture, 1904 – 1984, buildings like Shell House are now vulnerable to demolition themselves.

She argues too few Modern buildings are recognised through legislated listing and scheduling processes and believes New Zealand’s Modern heritage isn’t adequately valued overall.

On top of that, the age-old arguments against spending to strengthen or adaptively reuse heritage buildings in favour of better returns on new builds persist among many of today’s property developers.

The upshot is Wellington is now at risk of losing its Modern heritage too.

In 2014, Lower Hutt’s Horticultural Hall was demolished, followed by Wellington’s ICI House in 2017. In 2019, building owner Ryman Healthcare opted to demolish the best part of the former teachers’ college, an exemplar Brutalist complex in Karori.

Right now, the future of Wellington’s Gordon Wilson Flats hangs in the balance, despite appearing as a heritage item on the Wellington City Council’s district plan.

As we wander past the James Cook Hotel, an early local example of 1970s Brutalism, we reflect on the lead architect Graham Kofoed’s use of raw concrete, which Karen explains is characteristic of the approach.

Gathering on a patch of grass at the intersection of The Terrace and Everton Terrace, we come to our last stop on the tour.

Pointing across the road to Herbert Gardens, a Modernist apartment block built in 1965, Karen notes the emblematic floor to ceiling windows in each of the 52 apartments.

Back then, apartment blocks such as Herbert Gardens and Jellicoe Towers were built, in part, to fulfil the city’s vision of Wellington as a little Paris characterised by metropolitan-style living and good design for the masses.

From what we know now, it seems Wellingtonians weren’t quite ready for making the shift from the suburbs to the inner city, says Karen. But apartment living has definitely come into its own these days.

As we say our goodbyes, we agree it’s ironic – just as some of the ideals of Modernism are coming to the fore again – the built heritage that expressed those ideas is under threat.

What is Modern architecture?

Modern architecture is an architectural movement that became dominant in Europe and US in the 1920s and 30s, before being taken up globally. Modernism emphasised the new and was thought to be an expression of its age and of industrial means of production, drawing on innovative technologies of construction, particularly the use of glass, steel and reinforced concrete. It was gradually replaced by postmodern architecture in the 1980s.

Who safeguards Modern heritage?

In New Zealand, local authorities have the power to protect modern heritage, while Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga is responsible for the formal recognition of the country’s Modern heritage.

Internationally, Docomomo international is the working party for the documentation and conservation of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods of the Modern movement.

Around the world, each Docomomo working party (New Zealand has one chaired by Auckland-based Dr Phillip Hartley) is compiling a register of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods for its region, which is held in the archives of the Netherlands Architectural Institute in Rotterdam. To date, approximately 800 Modern heritage places are registered with Docomomo, representing more than 35 countries. Find out more at: www.docomomo.org.nz

This story was first published in Heritage New Zealand magazine.